Marry the problem

What startups, systems, and relationships taught me about commitment

“Just marry a white guy.”

“There’s always the spouse visa.”

“Why don’t you just get married?”

These were the jokes friends made when I shared how anxious I was about my visa runway. It didn't offend me. I knew they meant well. But the joke landed because it encapsulates my reality.

I do want to get married, but not for immigration. I want to choose someone, not end up with someone because I’m stuck. The visa is my problem to solve and I’m solving it.

Although I’ve never married someone before, I have married a problem.

A user problem.

I spoke to over 300 users in my first startup. This ranged from short chats, to deep dives, and late-night Zoom calls. In all these conversations, I obsessed over one question: Why isn’t therapy working?

More specifically: Why are Asians all around the world so prone to mental health issues?1

The research this startup demanded was so intense, intertwined, and all-consuming, that at one point, someone mistakenly called me Senie — the name of the startup, and the word I’d used to describe the ideal mentor or coach in our prototype.

That’s how deep the marriage to the problem went for me.

During my MSc in Management of Information Systems and Digital Innovation at LSE, one of my professors, Dr. Carsten Sørensen, said something I didn’t fully register with me at the time:

“Marry the problem, not the solution.”

I was in my 20s, had spent most of my life single, and didn’t fully grasp what he meant. Especially since he was referring to information systems, not relationships.

But Dr. Sørensen had been married for over 20 years and often spoke about his wife with obvious pride and affection. He understood the connection between systems and humans better than most.

In a 2008 paper with Lars Mathiassen, he references Wegner’s (1997) contrast between algorithms and objects in information processing:

“Algorithms are ‘sales contracts’ delivering an output in exchange for an input, while objects are ongoing ‘marriage contracts’. An object’s contract with its clients specifies its behavior for all contingencies of interaction (in sickness and in health) over the lifetime of the object (till death do us part).”

Maybe academics are more romantic than we give them credit for.

A sales contract is transactional, you show up, deliver, and leave.

But a marriage contract endures. It anticipates uncertainty. It demands resilience, adaptation, and forgiveness.

And maybe that’s what building really comes down to — whether it’s a company or a life: the willingness to be in a long-term relationship with a problem, a purpose, or a person. Not because it’s always rewarding, but because it’s yours to love through the chaos.

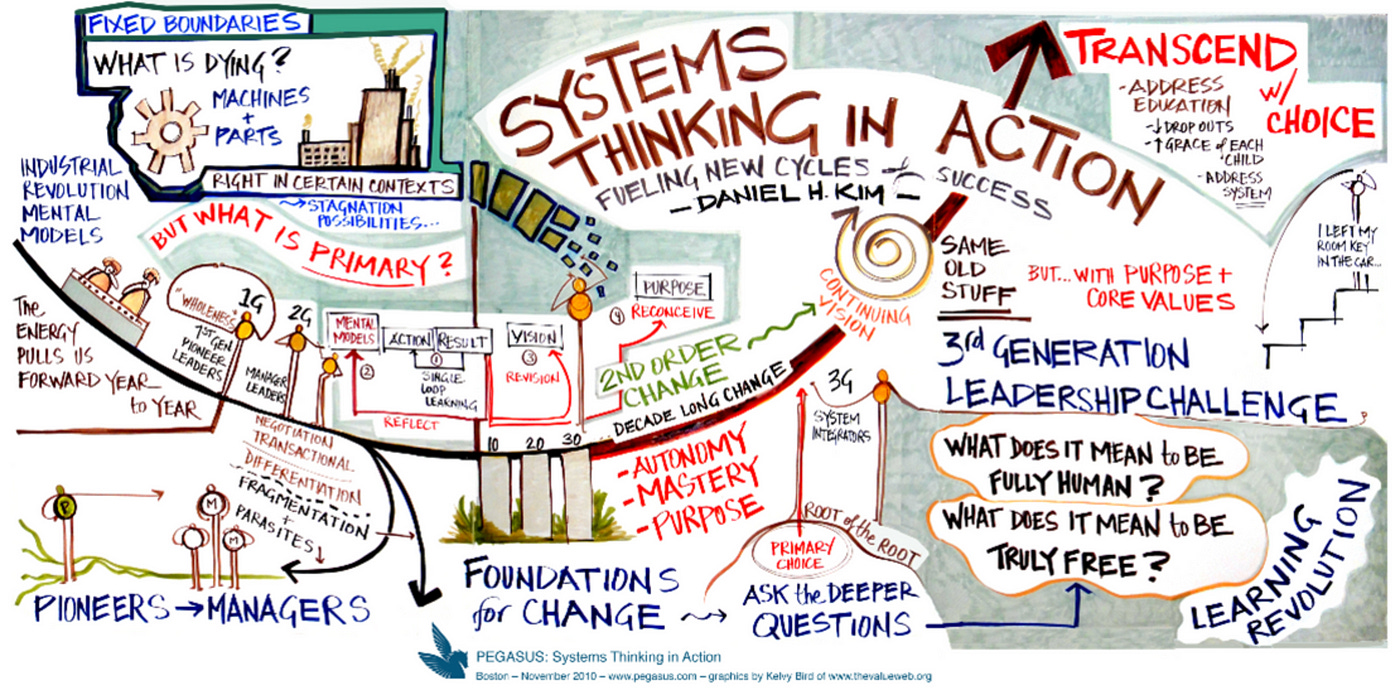

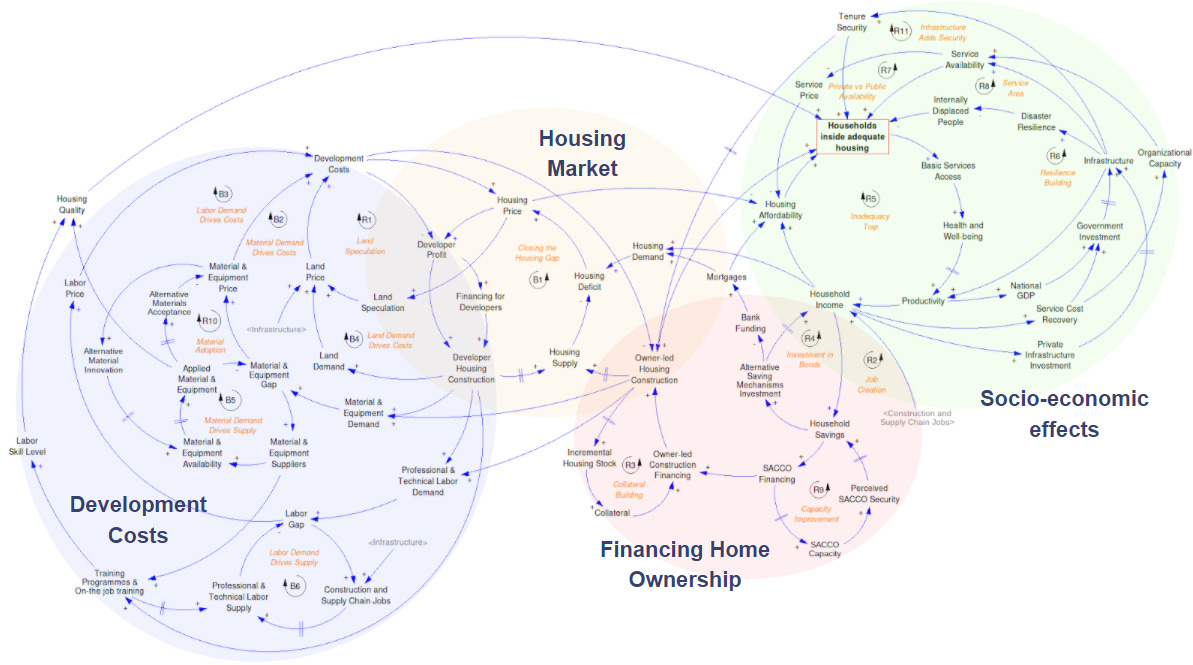

Like relationships, systems design is messy.

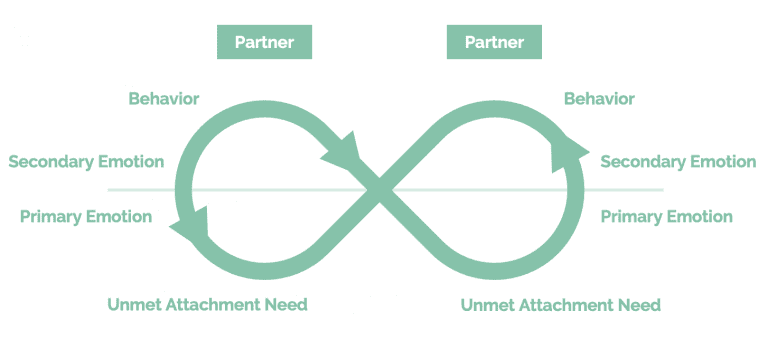

When something breaks down, it’s rarely about what’s visible. It’s usually about an unmet need.

And the way forward isn't to toss it out.

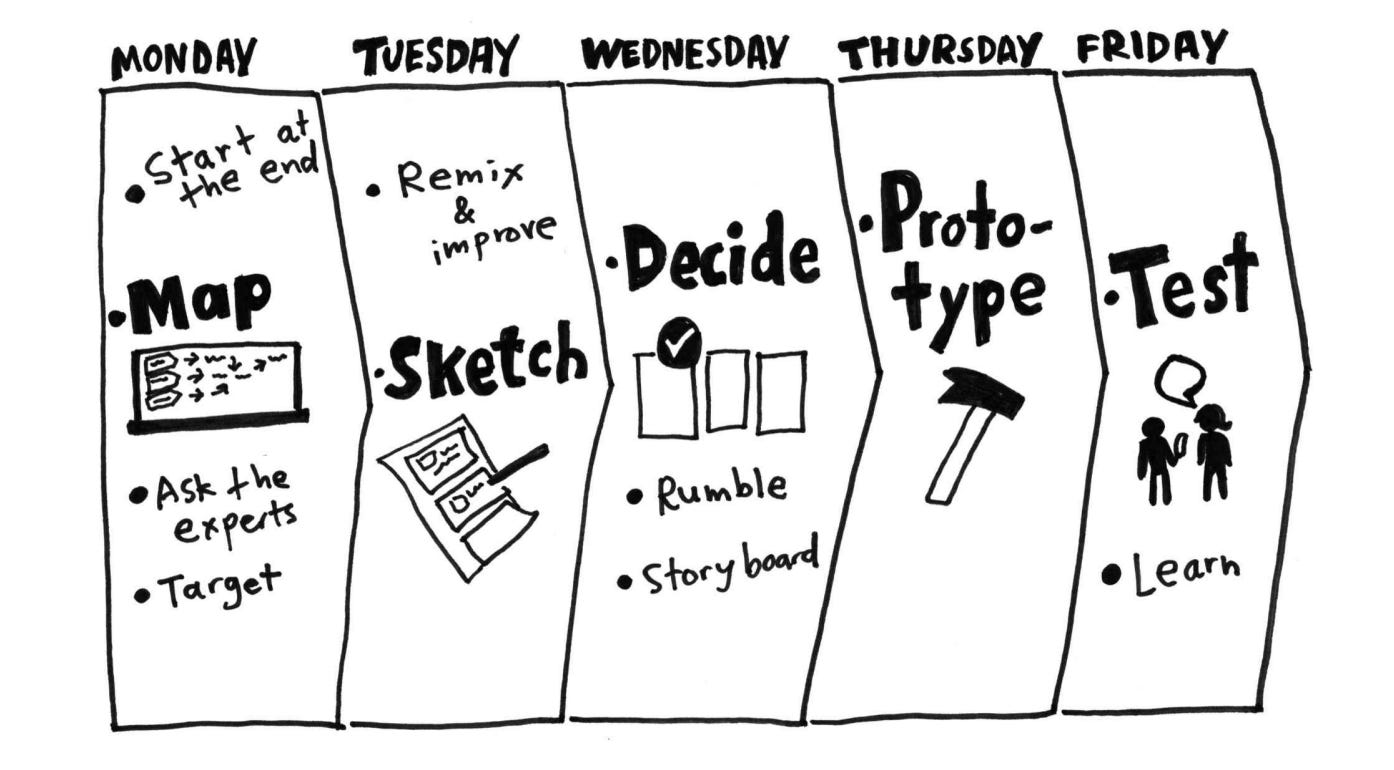

It's to listen, map it, redesign, test, and try again — like an ongoing sprint.

Because whether it’s a system or a relationship, real commitment means you stay curious, even when it’s hard. You don’t walk away at the first bug.

You debug. Together.

But why do marriages, or startups, fail?

Why do things fall apart despite beginning with so much hope?

Alain de Botton has a theory.

In Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person, he suggests that most of us don’t know ourselves nearly as well as we think we do. And that lack of self-knowledge quietly sabotages everything.

He put it like this:

“People thought many things were wrong with you but they weren’t going to bother telling you. They just left. The knowledge is out there, but it’s not in you.”

We move through the world misreading our own patterns. We’re addicts, not always to substances, but to anything that keeps us distracted from our inner world.

And the cost? If we never sit with ourselves, we can’t build anything meaningful with anyone else, not a company, not a marriage, not a life.

But the journey wasn't a waste. When I eventually stepped away from the startup, I started therapy.

After all those interviews, one thing had become painfully clear: for many Asians and minority communities, therapy often fails not because the tools are broken, but because the context is missing.

What helped me most was finding someone who could understand my parents, or at least the world they came from. Because you can’t untangle your own patterns without first understanding the people who shaped them.

One of my former flatmates, the person who inspired the original idea, once told me after yet another therapy session that didn’t land:

“I just want to feel understood.”

So when it came to finding my own therapist, I wasn’t scanning credentials or chasing prestige. I looked for someone I could see in person. Someone who understood cultural nuance. Someone who could read between the lines.

What Chinese people call “眼缘” (yǎn yuán): that unspoken connection. The feeling that someone sees you, without you having to explain.

Commitment, when done right, is beautiful.

My married friends, like Joyce Ding and Raphael Chow, are often the first to call me out — no filters, no sugarcoating.

They’ve taught me that love is a mirror: it reflects your blind spots, challenges your ego, and asks you to grow.

Real relationships give you a live feedback loop. They make you sharper, more self-aware, more human. They make you a better teacher and a better student.

And showing up together to fix what’s broken takes far more courage than simply walking away.

As Alain de Botton said:

“I need you. I’m not invincible. I am soft here. And I hope you won’t break me.”

My grandmother had an arranged marriage.

A founder once told me that Entrepreneurs First felt like one too — being forced to choose a founder in a matter of weeks.

At first, I disagreed. In my experience with the FIND program, you do get to choose your team.

But I think I understand his point now: commitment under pressure reveals who's truly ready to build something that lasts.

When I asked a Chinese student, married at 22, why she tied the knot so young, she said:

“It’s just a contract between stakeholders with shared interests.”

And honestly? She wasn’t wrong. Marriage is, in many ways, a long-term partnership agreement.

A South African–Belgian artist once asked me, completely deadpan:

“Why would you even want to get married? It’s just for taxes or a passport.”

She’s been with her partner for years, no ring, no paperwork, and she’s happy.

Well… I guess it’s nice to have someone to do taxes with.

Edited by a “cute white guy.”

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/asian-american-youth-increase-suicide-rcna167592

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/feb/10/therapy-failing-bme-patients-mental-health-counselling

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/your-stories/talking-about-mental-health-in-asian-communities/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-024-02864-5

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1071736/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10064227/