I'm a leftover woman

From marriage markets to modern feminism.

“Do you have a car? Do you have a house?”

That’s the question people commonly ask in Shanghai. It’s not meant to be offensive. It’s just direct, a shorthand for assessing someone’s “readiness” for adult life. And when it came to dating, things could be just as… pragmatic.

A while ago, a LinkedIn connection messaged me after reading my “Cute Asian Girl” piece. We finally had a chat online. He told me he used to study social issues in China while attending high school in the UK and recommended a few documentaries to me.

They were all about “leftover women” (Shèngnǚ 剩女), a label for women who remain unmarried past their late twenties.

It took me a week to realize: oh. I guess I fit that label now.

Wait… did he just subtly tell me I’m a leftover woman?

When I was 17, a controversial reality show called Bride Wannabes (盛女爱作战) swept across Hong Kong. The show followed several older women navigating the dating scene, highlighting how difficult it was for professional women to find love in their 30s. They were dubbed “three high women,” a term that refers to women with high education, high income, and high age. The internet exploded with mockery and memes.

Later, when I was in Shanghai, the drama Nothing But Thirty (《三十而已》) was everywhere. One character, Manni, was an ambitious saleswoman at a luxury store, trying to climb the social ladder through marriage.

“I just want to find someone rich, interesting and handsome.”

The first time I encountered the idea of a “marriage market” in China was in 2017, during a trip to Chengdu.

I was walking through a park when I noticed aunties and uncles putting up posters, basically physical dating profiles, to help single men and women find a match. I was 22 and backpacking a lot back then. Marriage wasn’t something I was thinking about at all.

As I strolled around, a guy shyly handed me a piece of paper and walked away. It was a small printout with his age, job, what he was looking for, and his phone number. It was actually very sweet. I still remember one line: he wrote that he wanted to find someone to love and take care of each other while living a simple life.

A marriage market is just one of those things you stumble upon in People’s Square, a place that looks like any other park, until you realize the umbrellas are covered in dating résumés.

“Bamboo doors match with bamboo doors; wooden doors match with wooden doors.” (竹门对竹门,木门对木门。)

It’s a Chinese traditional metaphor about social compatibility in marriage or relationships, often referring to how people should pair with others of similar family background, social class, or economic status.

At the marriage market, parents gather to exchange detailed profiles of their children, age, height, job, income, education, family values, personality traits, even Chinese zodiac signs. Education, in particular, carries enormous weight.

Since the late 1990s, rising university enrollment has made educational prestige a key filter in Chinese relationships. Elite schools now shape not just careers, but marriages, reinforcing assortative mating and consolidating privilege. Well-educated couples tend to invest heavily in their children, passing down status and opportunity.

Chinese pragmatism around dating can feel jarring to outsiders. But beneath it lies a long-standing cultural logic, one still shaped by deeply gendered expectations.

“Men fear choosing the wrong career; women fear marrying the wrong man.” (男怕入错行,女怕嫁错郎。)

Growing up, I was reminded of all these beliefs again and again in a traditional family.

On The Innovation Conversation podcast, someone asked how, as someone coming from one of Hong Kong’s oldest lineage families, I could be affected by traditional expectations. I answered honestly:

“I’ve been told I should be married since I was 23. And to this day, I’m still considered a disappointment.”

Investors poured over $5.3 billion into dating and social networking companies in China in 2020. On a recent trip to Shenzhen, I noticed how common marriage counseling studios have become. You can spot them easily next to a beauty salon.

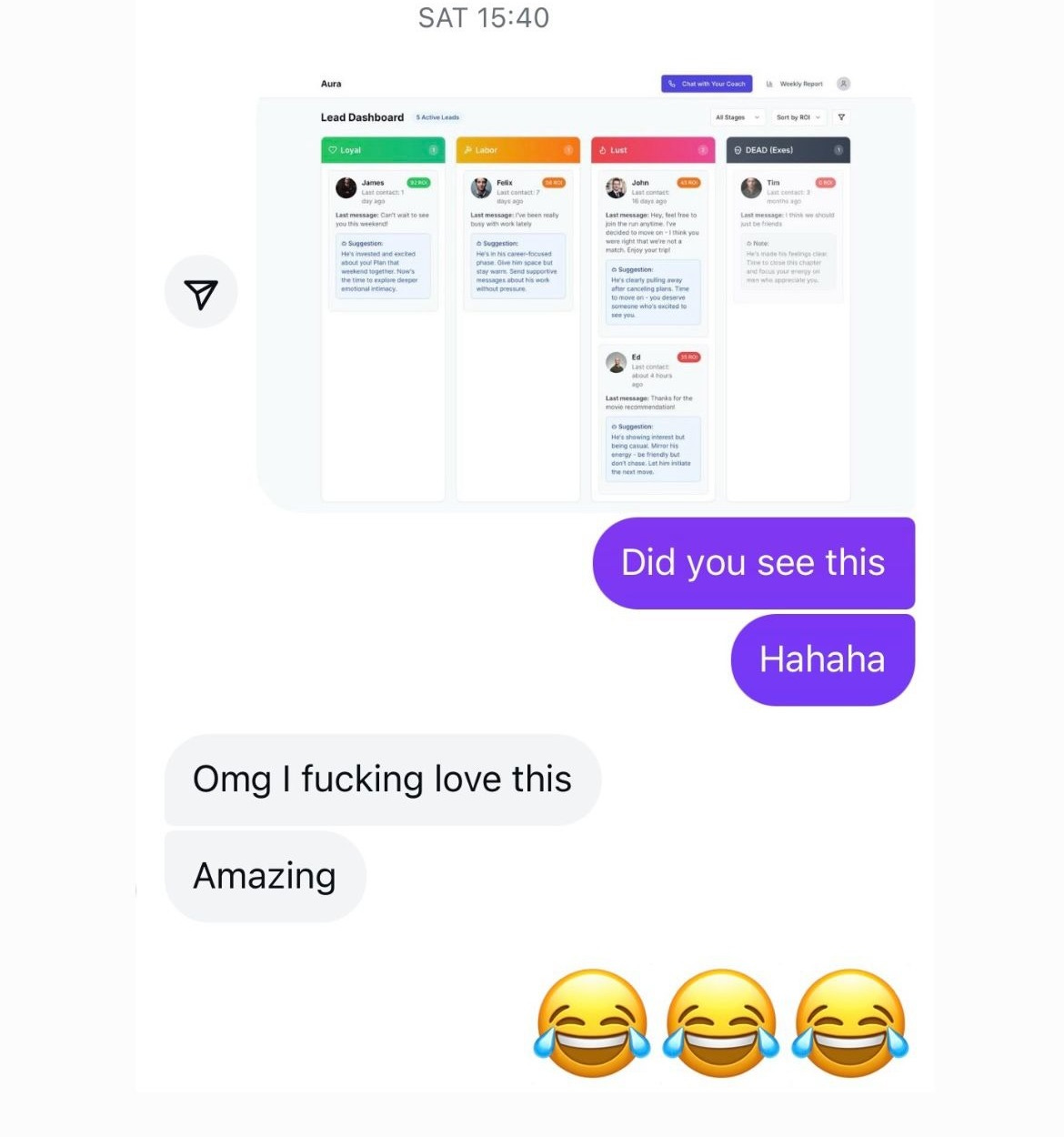

Given how often my single girlfriends complain about dating, it honestly feels like a fun and meaningful problem to work on. I even built a dating CRM at a hackathon with two guys, and one of my friends absolutely loved the idea.

It’s a mistake to assume all Chinese women expect a man to have a house, car, and top degree.

China is vast, and regional cultures shape women’s values and expectations in very different ways. Shanghainese women are often seen as stylish and financially independent, frequently managing household finances. Beijing women are known for being outspoken and sharp, shaped by the capital’s intellectual culture. Guangdong women tend to be pragmatic and family-oriented, while Dongbei women are stereotyped as bold, humorous, and unafraid to take charge.

But one thing’s for sure, intercultural dating isn’t always easy. Western and Eastern expectations around love, commitment, and emotional responsibility can be very different.

A Western friend once told me about women who, after breaking up, would demand compensation for having had physical intimacy without marriage, as if unpaid emotional debt had to be settled. In more extreme cases, things escalated: toy snakes sent in retaliation, lawyers involved, even property damage. One friend had his place trashed and said he could still see his clothes hanging from a tree outside his window.

I used to feel uneasy knowing some single women moved to London just to find a man. They were in their late 30s, tired of dating in New York and Shanghai. I wondered, why make such a major life decision just to improve your odds of mating?

But I forgot something simple and deeply human: the desire to feel wanted and loved.

The same guy who first told me about the concept of a “leftover woman” also shared that he went through depression at 18. Growing up as one of the only Asian guys in an almost all-white school, he faced constant romantic rejection and it left a mark.

During my journey of interviewing users for my first startup a Chinese student who’s pausing university told me that she got eating disorder as she was PUA (a term in China used to describe manipulative, gaslighting behavior).

It’s important to remember: marriage isn’t a cure-all. Problems don’t vanish just because you tie the knot. In Nothing But Thirty, one character enjoys a glamorous trophy-wife life until her husband cheats. Another opts for stability and a quiet 9-to-5 marriage, only to end up divorced.

“They say marriage is a safe harbor but if everyone wants shelter, who’s willing to be the harbor?” (都说婚姻是避风港,都想避风谁当港啊?)

One thing I do believe: who you marry may be the single most important decision of your life, whether you’re a man or a woman.

The idea of a leftover woman is both a social label and a cultural judgment, reminding women that their value has an “expiry date.”

As a former One Child Nation, China is now home to a generation of women carrying the weight of being the only child, with the expectations of two parents and four grandparents resting on their shoulders. Despite the government's shift to a two-child, then three-child policy to combat the declining birth rate, social and economic pressures continue to discourage young people, especially women, from having children. The burden of care, career, and tradition often falls disproportionately on them.

On that same 2017 trip, I also traveled to Lugu Lake in Yunnan, home to the Mosuo people, often called the “Kingdom of Women.” In their matrilineal culture, women don’t marry in the traditional sense. Instead, children take their mother’s surname, and inheritance passes through the female line.

It was an unexpectedly eye-opening journey for me. I never would have guessed that a woman could be expected, or even allowed, to live such a completely different life.

Turning 30 didn’t feel nearly as dramatic as I imagined it would. If anything, the anxiety came before the birthday. This creeping fear that I hadn’t achieved enough, that I was somehow behind.

Now that I’m here, 30 feels… fine. I still feel young, energetic, and ready to start a new life, a new career, a new chapter anytime.

I may be leftover but I’m not left behind.