How much is your time worth?

Time: the real currency of career, love, and startups.

My first relationship ended after 6 months. At 20, the heartbreak felt enormous. I turned to the internet for comfort and found an oddly helpful way to put things into perspective.

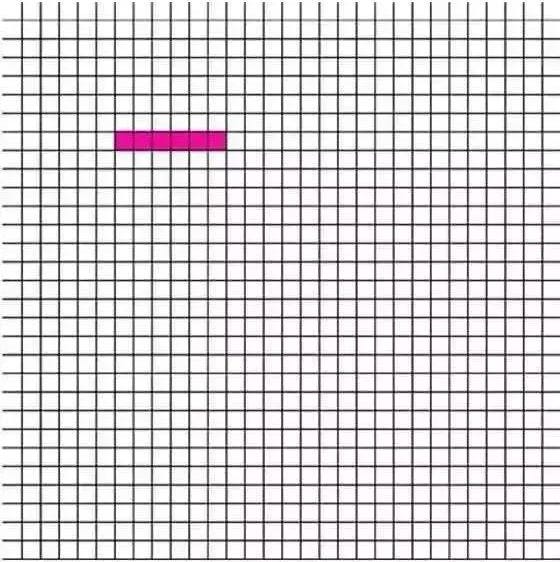

If we assume an average lifespan of 75 years, that’s just 900 months in total. Imagine drawing a 30 × 30 grid to represent an entire lifetime. Each square equals a month. 6 months? That’s just 6 tiny boxes:

But trust me, at the time, it felt like everything.

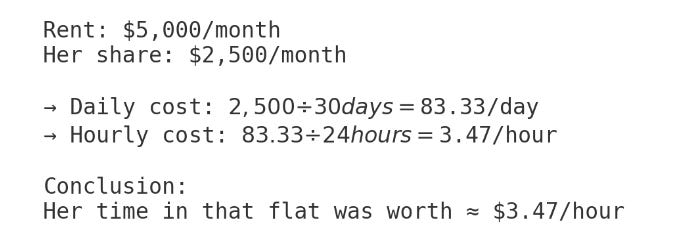

Funny enough, as a live-in Airbnb host for over a year, I’ve met quite a few newly single women who booked a stay after splitting with their partners. One guest had just moved out of her ex’s place in Canary Wharf, where she’d been living rent-free. Now she was struggling with both logistics and a quiet grief she couldn’t quite name.

As I listened, I couldn’t help but process it the only way I knew how: through numbers.

The rent for the flat was around $5,000 a month. Her half? About $2,500. Divide that by 30 days, then by 24 hours, and her time in that apartment was worth just $3.50 an hour.

I pay my therapist $190 an hour, my handyman $50, and my cleaning lady $19. Her emotional labor, meanwhile, was valued at just $3.50.

I’m not sure if it made her feel any better. But in my head, it made sense.

That kind of mental math might sound cold, maybe even extreme, but after years in consulting, it had become second nature. In that world, every hour had to be logged, every task assigned a rate. Your value wasn’t just in what you did, but how much time you could bill.

In Biglaw, one associate’s hour can run a client $500. For senior partners, it’s $1,000 or more. That’s the agency model: time is money, and the clock is always ticking.

What’s striking is how many people in high-achieving careers (myself included) start to internalize this logic. I once dated a dentist who had a classic rivalry with his investment banker brother. More than once, he’d say, “If you count the hours, my rate’s actually higher.”

My previous cofounder was a software engineer. He never understood my obsession with timesheets and hourly value. For him, productivity wasn’t tracked in minutes — it was measured by what you could build once and scale infinitely. I saw time through consulting’s 15-minute increments; he saw it through code and leverage. We weren’t just in different roles, we were living by different clocks.

The reality is, in the startup game, the value I create isn’t tied to how many hours I work, it’s tied to what those hours produce. It’s about leverage: minimizing input (my time) while maximizing output (traction). That’s the metric that matters now.

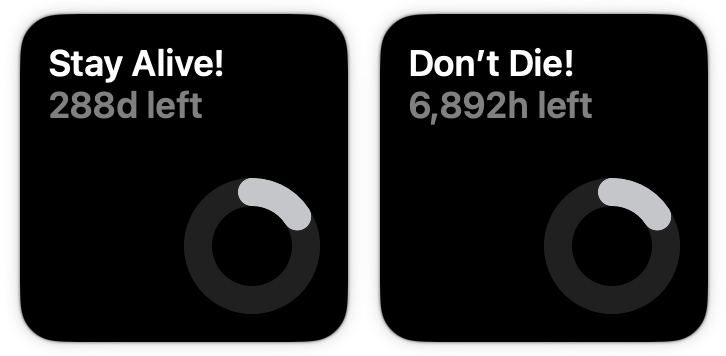

Y Combinator’s Paul Graham once wrote a piece called How Not to Die, offering advice to early-stage startups. Dalton Caldwell echoed the same on Lenny’s Podcast: “Just don’t die.” Because sometimes, how you spend your hours really is the difference between your startup failing, surviving, or thriving.

I use Pretty Progress countdown widgets on my MacBook and it looks like this:

So after all, I do think those years of consulting shaped something valuable in me. It drilled in a sense of urgency around time.

I’m particularly drawn to the topic of time because my first startup was a mentorship and coaching platform, essentially a place where people could sell their time, much like Intro, Mentorcam and Meander.

Successful founders often have their own philosophies about time. Jeff Bezos talks about “minimizing the number of regrets” he’ll have at the end of his life, while Steve Jobs famously said we should “live each day as if it were our last.”

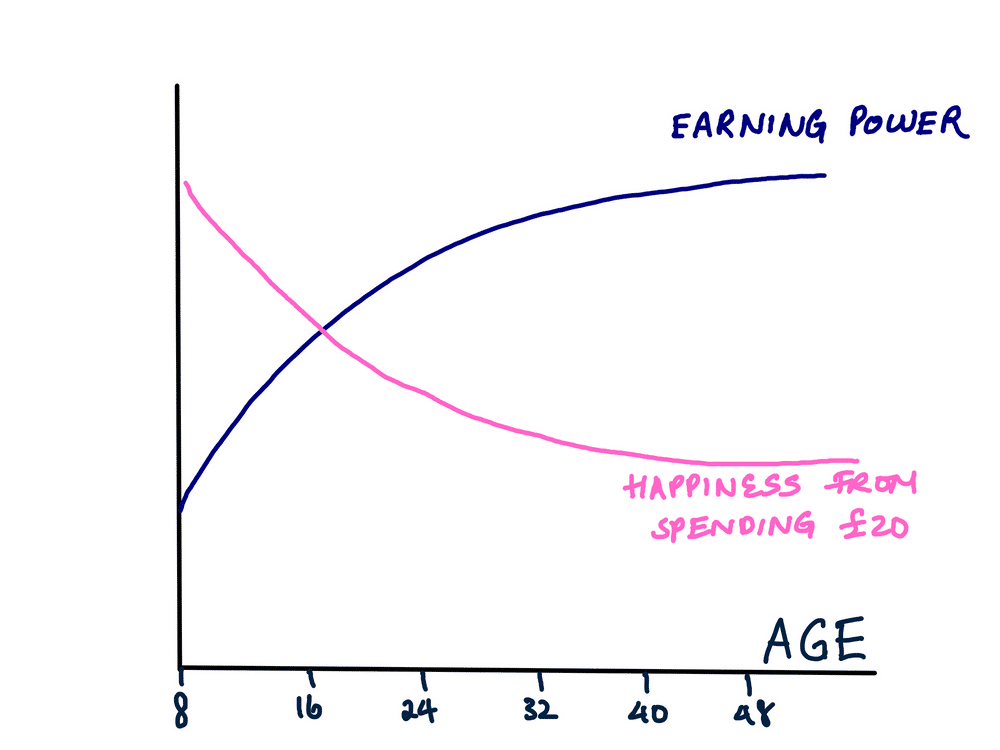

What’s frustrating about being an employee in an agency business model is this: even as your income rises over time, the older you get, the harder it becomes to fully enjoy what that money can buy.

I’ve hit that point. Spending money doesn’t excite me the way it used to.

I’ve been a full-time founder for 1.5 years now. That’s 18 boxes on the life grid.

Inside these 18 boxes were tears and sweat chasing something that may never work. The hardest part wasn’t the workload; it was the shift from predictable paychecks to showing up every day with no guaranteed reward.

At times, it feels like I’m paying tuition in the school of real life, buying back my time in exchange for hard-earned lessons.

When I was young, I dreamed of being able to time travel. I loved movies like The Time Traveler’s Wife and About Time, both starring Rachel McAdams. But real life isn’t a film, and the truth is, none of us can buy our time back. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. As the ancient Chinese saying goes:

“一寸光阴一寸金,寸金难买寸光阴。”

“An inch of time is worth an inch of gold, but an inch of gold cannot buy an inch of time.”

Recently, I’ve been tempted by the idea of returning to stability. I sought advice from a senior leader at a top investment bank. He told me, “10 years ago, I was in your shoes. I wish I had taken more risks.”

Throughout my twenties, I tried to make the most of my time — work hard, play hard. The book If You Don’t Do It Now, You’ll Never Do It (《有些事现在不做,一辈子都不会做了》) had a big influence on me.

Nvidia’s Jensen Huang likes to tell the story of a gardener who said, “I have cared for my garden for 25 years. I have plenty of time.” And of course, there’s Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-Hour Rule. Mastery, it seems, always comes back to time.

We never know what’s going on behind the scenes of so-called overnight success. Just like the old saying goes:

“台上一分钟,台下十年功。”

“One minute on stage takes ten years of practice offstage.”

I think managing one’s own allocation of time and attention in unstructured work (which creating something always is) is really tough. Particularly if there is no direct feedback loop on how effectively each hour spent doing a task moves you toward your goal. The consultancy / agency model — which structures work neatly based on a revenue / profitability target — didn’t teach me anything about how to do that better. How do you go about it?

"her time in that apartment was worth just $3.50 an hour"

The cost of the apartment to her was just $3.50; the value of the apartment to her is her marginal revenue product from it methinks