Be cringe!

The price of progress.

“Can you speak Cantonese? I’m tired of hearing your English.”

I’ve heard that line a few times in my life.

As someone surrounded by many native English speakers in Hong Kong, it stings, especially when it comes from someone who looks like me, who grew up in the same place, in the same culture.

The people who make comments like that are usually perfectionists who’re hard on themselves, and even harder on others.

And I know that because… well, I can be like that too.

Some of the nicest people I’ve worked with weren’t locals. They guided me, gave me thoughtful advice when I needed it most, and never once made fun of my English.

It’s strange, then, that I often felt more supported by westerners than by my own people.

Let’s be honest: Hong Kong people can be mean. If you didn’t know that already, now you do.

Our parents would tell us it would've been better to give birth to Char Siu (叉燒), barbecue pork, than to us. That’s a real saying:

“Better to have birthed pork than you.” (生嚿叉燒好過生你)

And some of us even grew up with physical punishment. I recently had an open conversation with friends and realized how many of us share this collective trauma. The feather duster (雞毛掃) is practically a symbol of our childhoods. My grandmother beat me with one so often that all the feathers eventually came off and just a bare stick was left.

And in local schools? Things aren’t all that different.

Hong Kong YouTuber Emi Wong recently shared an experience from her school days: one time, she and a friend forgot to fully button their school uniforms. As punishment, they were made to stand in front of the entire school. Later, a teacher told Emi’s mother that

“in the past, only prostitutes dressed like that.”

One local student even shared her experience with the Education Bureau, comparing her time in a local school to that in an international school. She said studying in a local school felt like being in a prison: she had to sit still, wasn’t allowed to eat, drink, or even use the bathroom during class and she was constantly buried in homework.

We’re being reduced, shaped and minimized into a version of ourselves that fits in. My grandmother used to remind me:

“One who is in the forefront will be attacked first.” (槍打出頭鳥)

Maybe that’s why it’s not always easy for us to step outside our comfort zones. Why we judge ourselves (and others) so harshly. Why we second-guess every move.

“It’s cringe."

That’s the easiest excuse we tell ourselves to stop trying. And it’s the easiest judgment we cast on others who dare to try.

I’ve been publishing essays weekly for three months and posting on LinkedIn daily for two months. People have started reaching out, inviting me to events, and connecting me with others. This has become my way of showing my value and sharing the information I had once withheld.

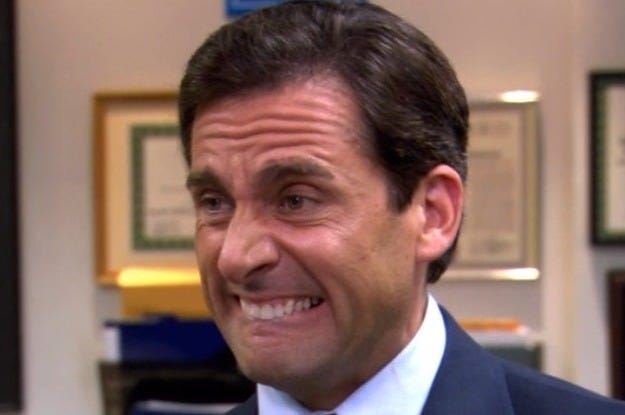

And trust me, my face looks like this sometimes.

But here’s the thing I’ve come to realize:

Cringe is a gift.

It means you’ve grown. It means you’re not stuck in the same emotional or creative place. Cringe is a receipt. A receipt that proves you tried. That you cared.

Maybe the problem was never cringe. Maybe the real issue was fear, fear of being bad at something, fear of being seen before we’re “ready,” fear of failing in public.

I once had a YouTube channel full of chaotic and embarrassing videos from university. Me talking to the camera, making montages, romanticizing little moments of life. I deleted it all. Too cringey.

But what I forgot was this:

Cringe is the cost of consistency.

Cringe is the down payment on progress. Cringe means you had the guts to start.

So yeah, be cringe. Be a little bit silly.

I mean, what do I know?

After all, I’m just a cute Asian girl.

(And by the way, both my English and Mandarin have improved a lot over the years.)

My new MacBook had an accident at a hackathon and now it’s like this… yet, I still published :)